note Note générale

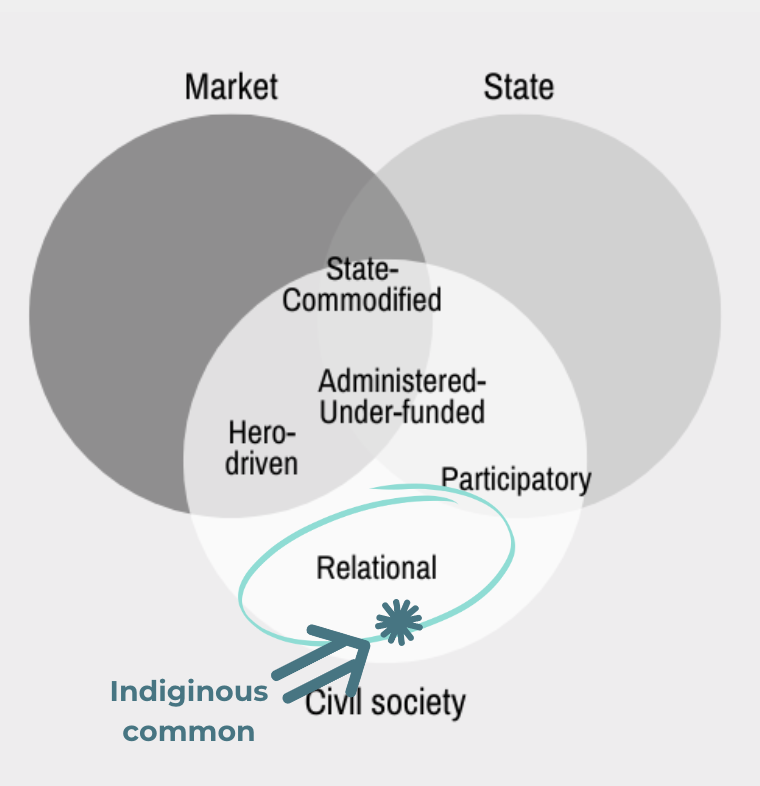

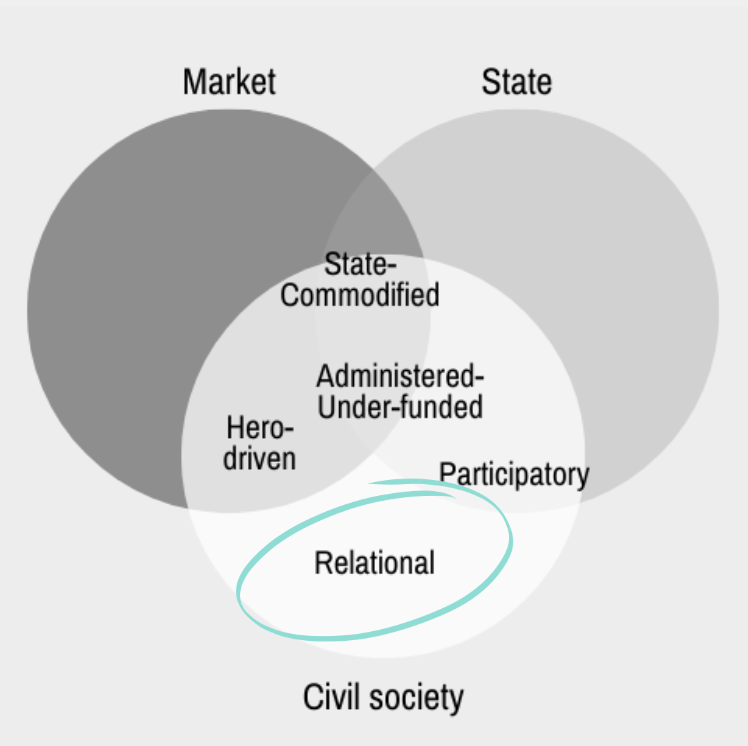

Typology of Emerging Commoning Practices in Quebec.

This note is part of the Commoning Beyond Growth Workshop, which took place in Nottingham from June 5 to 7, 2024.

Cette note s'inscrit dans le colloque le Commoning au-delà de la croissance, qui a eu lieu à Nottingham du 5 au 7 juin 2024.

💡 Une traduction de la note en français est disponible plus bas.

Today, I will present to you the result of my doctoral research : a typology of commoning practices that are currently emerging in Quebec (Canada).

While commons are often discussed in a theoretical context, usually focusing on a few similar cases, my research aimed to conduct empirical studies on a highly diverse set of commons. Additionally, while commons are typically presented as resources to manage, I focused on studying the process of commoning.

In 2018, commoning was minimally theorized. During my literature review, Euler’s (2018) article stood out by providing a concrete conceptualization of commoning based on different dimensions. Therefore, I went to meet him to better understand his proposal.

My objective was to operationalize his theoretical framework in order to create a survey that would be administered to potential commons in Quebec. I wanted to verify if and how the proposed dimensions of commoning were being mobilized by the commoners. And what was the impact of the state and the market on these practices.

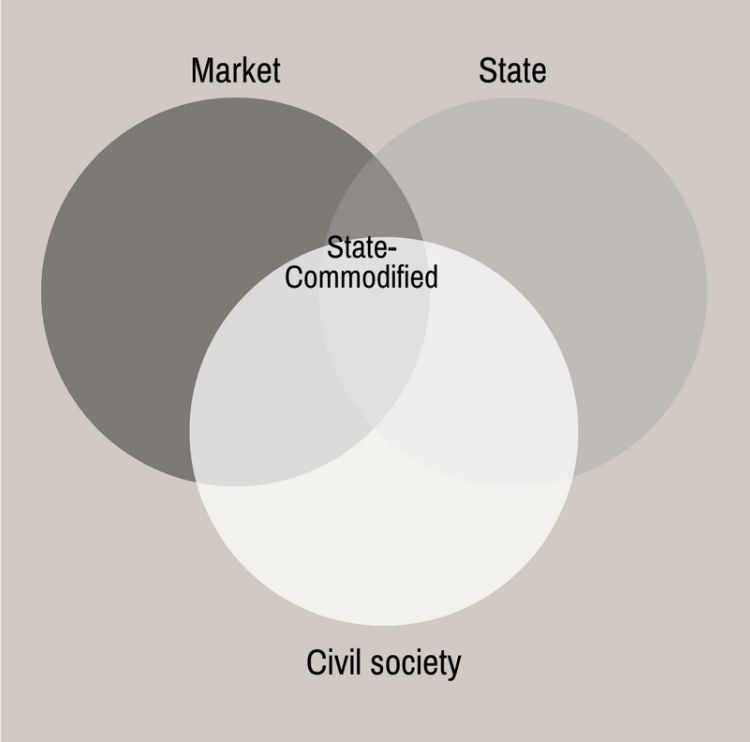

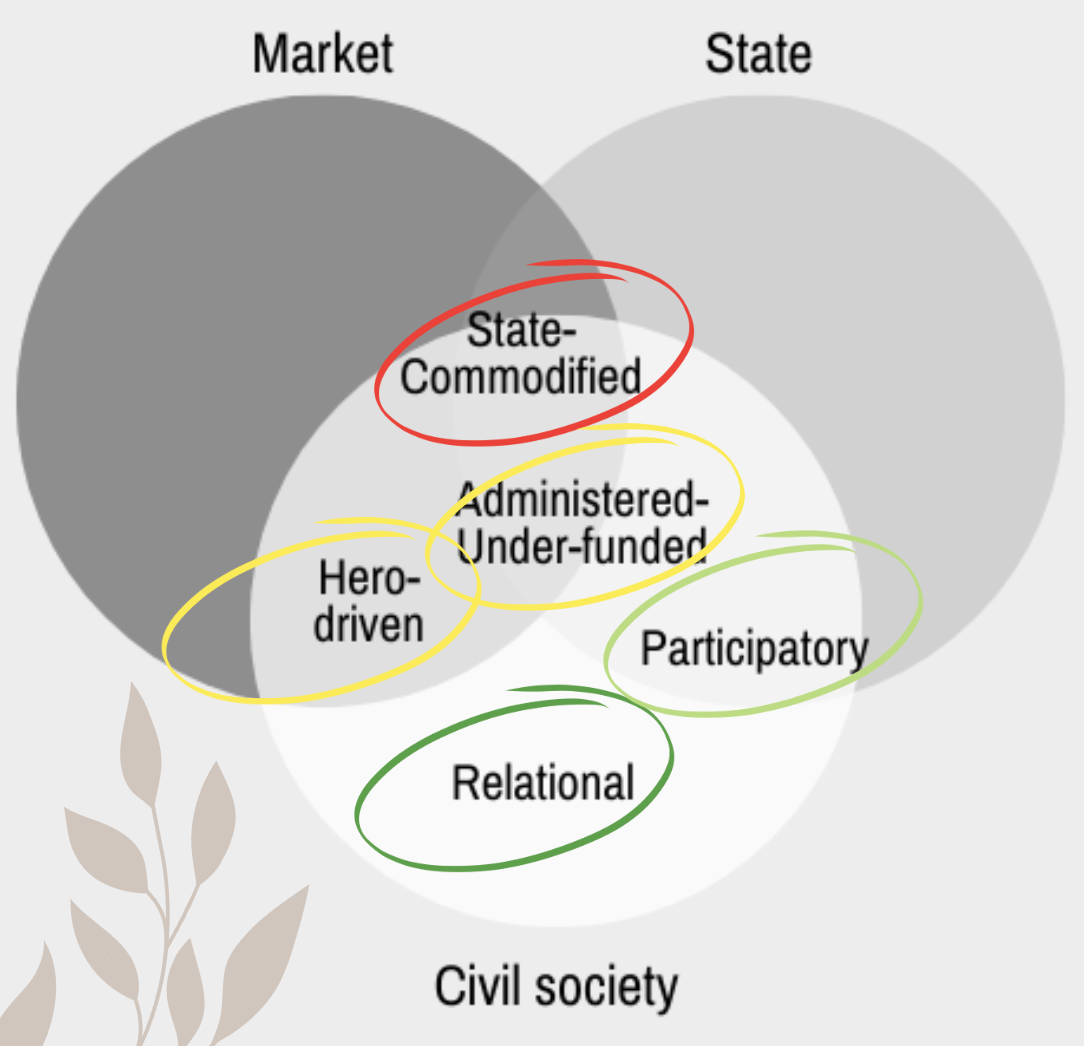

For me, creating a typology of commoning was crucial, because there are no pure commons or pure commoning in capitalist societies (Euler, 2018; Le Roy, 2021). Therefore, the interaction of commons with the state, the market, and consumers inevitably influences the commoning practices we try to implement (Le Roy, 2021).

Given that commons are not "pure," they are not uniform, and their practices do not all present the same transformative capacities (Hollender, 2016). So creating a typology of emerging commoning practices seemed to me an excellent way to avoid generalizing commons or commoning under a single definition.

Therefore, My research aimed to

- define what emerging commoning practices exist in Quebec and

- what are the main types that would help distinguish them better

- what conditions need to be put in place to create an ecosystem conducive to their emergence?

Directory

I have created a directory of 300 potential commons through:

- Social and solidarity economy

- Community organizations

- Informal citizen groups

- Social movements

- Indigenous initiatives

Surveys

70 surveys conducted by phone:

- 50% in city

- 50% in country

20 different sectors of activity:

- Agriculture and food

- Care and health

- Territorialized approach

- Education

- Time banks, local currencies

- Art and culture

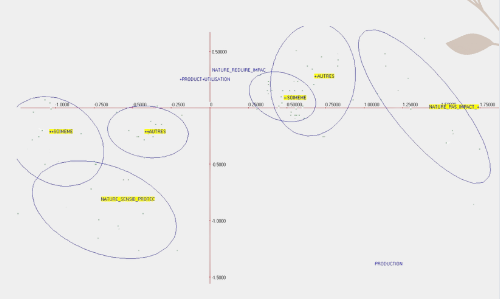

For the analysis of the data

I used the French approach to data analysis. Developed by mathematician Benzécri in the 1960s and notably used by Bourdieu.

A visual method that projects on the same factorial plane

- Individuals who have responded similarly

- Similar responses that have been provided

The resulting typology does not come from me but from the data itself.

Typology

5 ideal types has emerged from the data:

- State-commodified

- Administred

- Hero-driven

- Participatory

- Relational

4 factors explain the typology

- Autonomy from the State

- Autonomy from the Capital

- Delegative vs Participative governance

- Protective relation to nature

State-commodified

5 projects: Early Childhood Center (CPE), Prehospital Care Cooperative, Transport Cooperative

The analysis highlighted five highly institutionalized projects that stood out from the rest. These projects were mostly run by employees, and many started as government programs or were private companies that became worker cooperatives.

- Pricing strategy: set by the government

- Autonomy from the government: little to none

- Government-initiated project

- Relationship with businesses: competition

- Decision-making: by majority

- 30 to 50 employees

Administred-Under-funded

24 projects: 5 health coop, 3 cultural/sports centers, 2 housing coop, 1 telecom. coop, 2 grocery stores

This group, the largest, seems to closely resemble the more institutionalized social economy, particularly when it involves healthcare or social services. Many of these projects rely on expensive infrastructure or professional sectors (like health and construction), which explains their high need for funding. They have many employees, but also volunteers. Decisions are made by a group of delegates, usually by consensus or unanimity. These projects have little independence from their funders and deal with very bureaucratic and institutionalized financing.

- Decision-making: group of delegates

- Decisions: consensus or unanimity

- Little autonomy from funders

- Easy to participate in production

- Presence of power dynamics

- Funded by grants

- Little connection with the surrounding community

Hero-driven

13 projects : Cultural projects, Social change project for racialized youth, Learning center for marginalized youth, Telecom. cooperative, Agricultural projects, Open source digital platforms

The analyses show that Initiatives with little support from the state and community often depend on one or a few strong leaders. While it's normal to have a dedicated core group at the beginning, it's important to create more decentralized governance to avoid relying too much on a single leader, like in typical startup models.

- Difficult to participate in production

- Decision-making: founders

- Mixed impact on oneself

- Constrained by the need to be profitable

- Difficult to leave the project

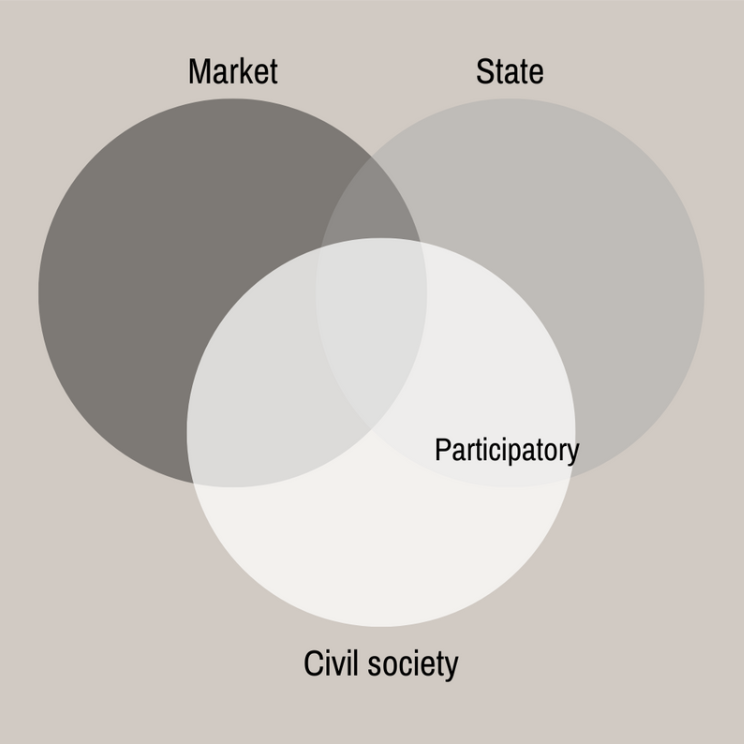

Participatory

11 projects: Urban agriculture projects, Community geothermal project, Citizen public space, Transition initiative, Rural school

When local governments and communities work together on non-market projects (like community gardens, green alleys, and rural schools), interesting practices develop. Employees and volunteers team up, interact actively with the local community, and set up governance methods that encourage as many people as possible to participate.

- Monthly or weekly activities with the surrounding community

- Decision-making: everyone by consent

- ++ ecological project

- Relation of cooperation with the local government

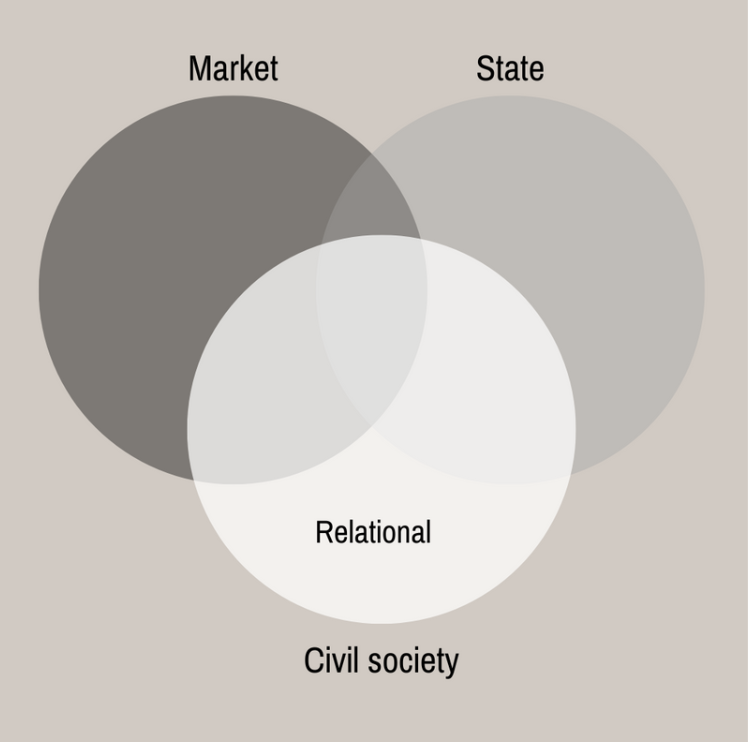

Relational

17 projects: Indigenous independence project, Intentional community, Local currencies, Time bank, Transition initiative, Citizen integration of refugees

Here, I have seen the most radical and forward-thinking practices. These commons are very independent from the state, capital, and their funders. They have few employees but many volunteers, and minimal market relations. When prices are involved, they are set to self-finance the projects or are voluntary contributions. Decisions are made by anyone willing to join through committees, which are open to all.

- Autonomous from funders and government

- Not constrained by the need to be profitable

- Easy to leave

- Difficult to use

- Very positive impact on oneself

- No internal power dynamics

Commoning practices that are neither uniform nor pure

These results confirm that there are no "pure" commoning practices. When we look at the 5 types of practices,

- State-commodified : I don't think we can consider state-controlled and market-driven practices as commoning.

- Regarding administred and hero-driven practices : I believe they have good potential to develop more commoning, but I've noticed that the participants in these projects aspire to more commoning, but it's currently very difficult for them. On one hand, commons are not legally recognized today, making it hard to organize as such. On the other hand, there are few tools suited for commons, and often these projects are forced to use templates and tools from private entrepreneurship.

- Regarding participatory practices : they seem to have several characteristics highlighted by Euler, even with state support. Many of these projects resemble public-commons partnerships, where local governments allow local communities to take care of public spaces.

- Finally, it is within relational practices that Euler's dimensions are most explicitly found.

So we can observe that the autonomy from capital and funders is an important factors to allow the emergence of commoning practices.

What conditions ?

From this perspective, what conditions need to be put in place to create an ecosystem conducive to the emergence of the most «pure» commoning practices ?

What Legal Form for Commons?

The NPO form was more popular than the cooperative form and seems to facilitate commoning practices.

Many relational commons prefer to have no legal form at all.

Possible solutions :

- Evolve formal legal forms (Co-op, NPO) to allow more decentralized governance (less power within the Board of Directors).

- Support commons without forcing them to adopt a formal legal form (e.g., collaboration pacts in Italy).

What Characteristics for Public-Commons Partnerships?

What Administred commons could learn from Participatory commons?

- Do not indebt the commons: provide free access to common infrastructures.

- Allow collaboration pacts with informal groups.

- Favor partnerships at the local government level rather than national.

- Beware of state disengagement: public-commons partnerships should not become a way for the state to shirk its responsibilities.

What Tools to Support and (Re)Develop Commoning Practices

What would help Hero-driven and Administred commons to develop more radical commoning?

-

- Create a program to support the creation of commons or the transition from collaborative economy projects to the commons economy (e.g., La Communificadora in Barcelona).

- Mobilize appropriate tools designed for commons (e.g., The Commons Sustainability Model developed by the femProcomuns cooperative).

Decolonize the Commons

In my research, an indigenous commons makes me realize the importance of decolonizing the commons:

Which lessons the indigenous common could share ?

- Decolonizing the commons involves politicizing the commons, considering the colonial, patriarchal, and capitalist history of Western culture.

- Many colonial commons were created at the expense of Indigenous commons.

- How do the commons we create today support the emancipatory struggles of historically oppressed peoples?

Developing Our Emotional Maturity

And finally, the relational commons reveal that:

- It is essential to developpe communication skills and emotional maturity.

- It is only when we become aware of our incompleteness and our interdependence with others that we develop the capacity to overcome the conflicts inherent in all collaboration

- We need to learn how to heal

References

note Note(s) liée(s)

30 mars 2024

30 mars 2024

Références | Communs en émergence au Québec

30 mars 2024 21 février 2024

21 février 2024

Marie-Soleil L’Allier s'intéresse aux communs

21 février 2024 12 juin 2024

12 juin 2024

Presentation of the notebook | Commoning beyond growth

12 juin 2024Carnet(s) relié(s)

file_copy

32 notes

file_copy

32 notes

Commoning Beyond Growth

file_copy 32 notesAuteur·trice(s) de note

Compte(s) anonymisé(s)

Communauté liée

Commoning Beyond Growth

Plus d’informationsPublication

2 juillet 2024

Modification

2 juillet 2024 15:42

Licence

CC BY-NC-SA, sans utilisation commerciale autorisée - plus d'informations

Visibilité

public

Pour citer cette note

Anonyme. (2024). Typology of Emerging Commoning Practices in Quebec. Praxis (consulté le 2 juillet 2024), https://praxis.encommun.io/n/dtDR4PC1IKeKj-8_FU9mAWajQdE/.

shareCopier