note Note générale

Against the Common Good: the role of capitalist consumer culture

This note is part of the Commoning Beyond Growth Workshop, which took place in Nottingham from June 5 to 7, 2024.

Commoning theory has greatly enhanced understanding of the role of colonial and neo-colonial exploitation in the destruction of the commons. I here focus on the affluent consumerism propelled by that exploitation, reflect on its power, but also consider how emerging forms of disaffection with its negative aspects might foster support for commoning and degrowth initiatives in wealthy societies. Though presented as a model of the ‘good life’ for less developed communities, consumer culture is better seen, I contend, for what it has largely become: an engine for the enrichment of a corporate elite at the expense of the health of the planet and the well-being of most of its inhabitants. The paper concludes by reflecting on the form an ‘alternative hedonist’ politics of prosperity might take and the ways it could hook up with degrowth policies and more explicit and militant commoning activism.

Commoning issues have until recently related primarily to the exploitations of a long and still on-going history of colonial and post-colonial land-grabbing, dispossession and neo-liberal commercial expansion. There are also today global-wide issues relating to the knowledge commons, and to the urban commons and city spaces, new government initiatives and civil society experiments in commoning, and their use of the law or defiance of it. There are related questions now about legal challenges to states to act on issues like climate change and pollution and whether these could lay the foundations for commons-based practises. There are concerns with the dubious legality of various ‘grey’ areas of commoning, where some practises are more protected, others merely tolerated (squatting, for example, right to roam, the seizure of urban space for community projects).

And there is now, of course, a growing literature on the overall project of a cosmopolitan commoning as the desired sequel to and replacement for neo-liberal capitalism. This has particular bearing on the all important current debates on degrowth politics and economics and the role of a post-colonial and post-capitalist commons in global green renewal. Many contributors to it have refused to endorse occidentalist technologies as necessarily more ‘progressive’, and, indeed, have criticized what has been termed ‘the hegemony of technocratic rationality’ as fundamentally dehumanizing and indifferent to human suffering (Venn, 2006: 6-12, 35-8; cf. 2018: 112)). They have also alerted us to the ways in which environmental constraints are undermining the capitalist growth agenda and its established assumptions about development and human welfare. And they have shed light on the extent to which growth-driven ‘development’ projects pursued on the pretext of improved welfare or human rights, may contribute to the further pauperization and oppression of the already poor.

In presenting the commons as the space essential to resolving inequality and to checking encroaching privatisation, commons oriented theorists have insisted on the rupture with capitalist values and ways of living essential to the realisation of any fair and sustainable order [SLIDE 3] Amin and Howell, 2016; Caffenzis and Federici, 2014; Dardot and Laval, 2019; De Angelis, 2018; Gilbert, 2014; Mignolo, 2011; Terranova, 2015, Venn, 2006; 20018). Emancipation from capitalism, De Angelis argues, is not simply a matter of resistance to it, but of ‘constructing systems that actualise an aversion to its goals, that have alternative goals’ (De Angelis, 2018: 116). ‘“Decolonials,’ Mignolo tells us, ‘are not looking for alternative modernities, but for alternatives to modernity’ (Mignolo, 2011: xxviii). These theorists have also laid considerable stress on the transformations of subjectivity required to realise these alternatives. As Couze Venn put it in After Capital, ‘critiques of capitalism must target existing ways of life, socialities, subjectivities and the unequal relations of power inscribed in and sustained by them’ (Venn, 2018:4; cf. 2006: 77-121). We need, he writes, to ‘question so much of what we have come to take for granted as “natural”, inevitable, “modern”, “progressive”, desirable or right’ (Venn, 2018: 15). And that, of course, means challenging the whole idea of continuous economic expansion as essential – although I would argue, and I believe many commoning theorists would agree, that we need to make certain distinctions here [SLIDE 4]

How do we conceive of growth ?

However, when it comes to the ways in which this radical transformation or ‘gestalt switch’ might come about much of the focus in degrowth and commoning studies has been on the already existing forms of social activism within specific commoning projects around the world (especially in Latin America, Africa and Asia). Less attention has been paid to the promotion of alternative thinking on prosperity, progress and the ‘good life’ in the most affluent Western societies, and its potential role in subjective transformations of a kind to issue in greater solidarity with the most exploited global communities, more pressure for debt cancellation and other commoning supportive measures. It is in this area that my own arguments on ‘alternative hedonism’ and post-growth ways of living would seem to align most closely with those of commoning theorists.

Where my ‘alternative hedonism’ aligns with current commoning thinking…

[SLIDE 5] Like them, I am calling for a reconceptualization of ‘progress’ that has affinities with earlier romantic antipathies to modernity, but which avoids the puritanism and social conservatism associated with traditionalist cultures of resistance. Like them, I am arguing for ‘transformations of sociality and subjectivity’ insofar as I view a cultural revolution in thinking on welfare and prosperity as essential to the ‘revaluation of values’ through which any transition to a post-colonial and post-growth order can alone be carried through. But my main focus has been on the dialectic of such changes in rich societies, and especially the ways in which affluent consumer society may – in virtue of its own more negative aspects and the discontents engendered by them – be contributing to its own demise, or, at any rate, to a socio-economic reconstruction that proves to be both more eco-benign and more open to new commoning practices.

Clearly, the most scandalous, but also intransigent, obstacle to any commons based greening of the economy is inequality, this being both a major cause and an ongoing consequence of environmental breakdown.

The disparities between richer and poorer nations and peoples in the contribution to climate breakdown and environmental degradation

[SLIDE 6] Between 1990 and 2015, the richest ten percent of the global population accounted for over half the emissions added to the atmosphere. The richest one percent was responsible for 15 percent of emissions during this time – more than all the citizens of the EU and more than twice that of the poorest half of humanity (7 percent). Over the same period, annual emissions grew by 60 per cent, and the richest 10 percent blew one third of our remaining global 1.5C carbon budget, compared to just 4 percent for the poorest half of the population. If this wealthiest ten per cent were to reduce their emissions to only the average for the EU, total global emissions would fall by a quarter. But if the poorest third of the world population were to raise themselves above the $3.2 dollar-a-day poverty line, emissions would rise by a mere five per cent - about one third of the emissions of the richest one per cent (Chancel, Bothe and Voituriez, 2023).

Statistics of this kind, improbable as they ought to seem, are already such a staple of commentary on the current global condition that they risk becoming more glazed over than boggled at. But what they starkly reveal is the fact, as Adam Tooze has recently put it, that [SLIDE7]

half the world’s population, led by the top 10% of the income distribution – and, above all, by the global elite – drive a globe-spanning productive system that destabilises the environment for everyone. The worst effects are suffered by the poorest, and in the coming decades the impact will become progressively more extreme. And yet their poverty means they are virtually powerless to protect themselves. This is the triple inequality that defines the climate global equation: the disparity in responsibility for producing the problem; the disparity in experiencing the impacts of the climate crisis; and the disparity in the available resources for mitigation and adaptation (Adam Tooze, The climate emergency really is a new type of crisis – consider the ‘triple inequality’ at the heart of it. Guardian: 23 November 2023).

These statistics also indicate that ‘commoning’ conceived in the most abstract sense of wresting control of wealth and material resources from the grip – and accompanying ecological dereliction - of a relatively small corporate elite will be essential to any fairer and therefore more effective green renewal.

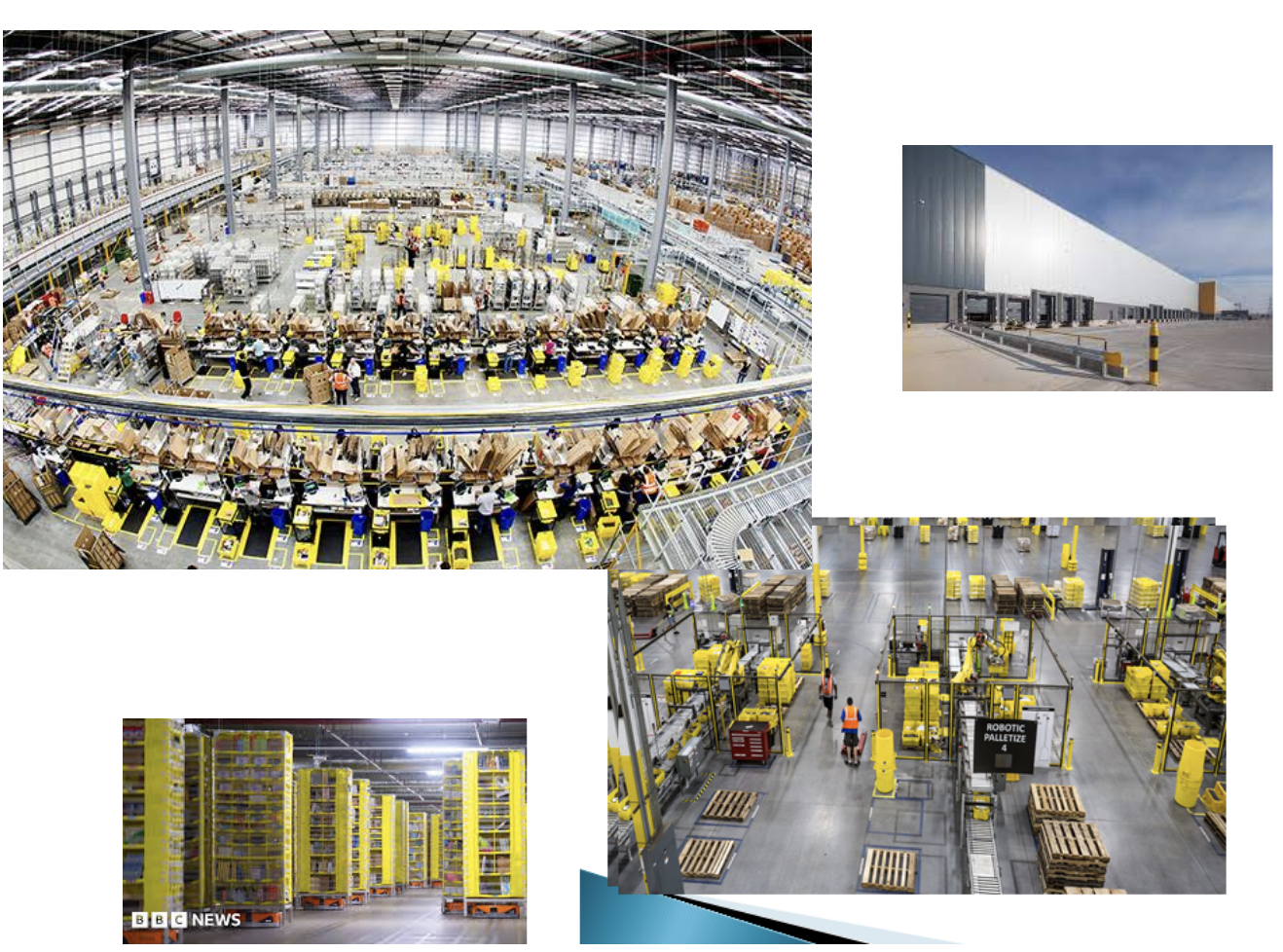

At the same time, if only in the absence to date of any serious consumer revolt or boycotting, they also indicate tolerance if not collusion on the part of a considerably larger number of the relatively affluent population. That Elon Musk is one of the richest on the planet is in part due to the very extensive and continuing support for a car culture that, even when electrified, is likely to prove unsustainable (as also dangerous and massively constraining on access to and use of space). That Jeff Bezos is likewise amassing his millions is due to the countless purchasing decisions of those who have so readily cooperated in the maintenance of Amazon’s gigantic fulfilment centres [SLIDES 8, 9]

: a form of compliance that - comparably, perhaps, to those who, we are told by the Egyptologists, gave their labour voluntarily over decades in the creation of the Giza pyramids - we do not know whether to view as emancipation or alienation; as freely conceived and realised desire or abject enthrallment to false fetishes. (Obviously there is a gaping difference in the ease with which these respective support systems have been provided !).

It is true that the power of Amazon, Tesla and the IT giants is very insidious, and to use online media at all is almost always to be party to it (Birch, 2020; Birch and Bronson, 2022; Bremmer, 2021; Galloway, 2018; Moore and Tambini,2021; Srnicek, 2016; Zuboff, 2019). There are also now growing numbers of disaffected consumers, including among them those who for ethical and environmental reasons resist conventional shopping practices, and are loathe to buy from Amazon. But it is also true, that it is mistaken to project the environmental troubles of our times as entirely accountable to the providing industries and their merchandising manipulations. The appetites and priority given to convenience of many customers in the richer nations, and the influence they exercise, have a major role in them, too, and any advocacy of transition to a fairer economic order needs to recognise that. There has long been a tendency among left critics of commodity society to emphasise the ‘unfree’ and manipulated quality of consumer desire, and to portray shoppers as ‘dupes’ of the capitalist market and its ‘culture industry’ rather than acknowledge their degree of autonomy and accountability. Something of this tendency lingers on in the outlook of campaigning movements such as Greenpeace, Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion – [SLIDE 10]

where the summons to action is primarily addressed to government to forswear fossil fuels rather than to consumers to forego driving or flying. Governments, of course, are alone in a position radically to transform current patterns of working and consumption, and are certainly to be condemned for their clamp down on environmental protest and persistent investment in fossil fuels. But consumers do also continue to expect to fill their tanks and fly to their holidays, and to treat ‘us’, the general public in affluent societies, as simply victims of ‘their’ entrepreneurial activities, is to provide too much of a cop out. To offer here but one recent example: without the take-up by consumers of ever bigger SUVs, global emissions from the motor industry would have fallen by 30% between 2010 and 2022, road accidents and pedestrian fatalities would also have been reduced (Global Fuel Economy Initiative, 2023; Horton, 2023; Hurst, 2023). The numbers, at any rate, who in polls will readily deplore the environmental horrors perpetrated by corporate power and government hardly seem matched by changes in individual consumer behaviour – or indeed in voting patterns.

It is for this reason, that in my argument for alternative hedonism I emphasise the cultural revolution in thinking about personal well-being and collective prosperity that will be needed as a prior condition of the emergence of any meaningful electoral support for a new national and ultimately global economic order. [SLIDE 11]

The ‘Alternative Hedonist’ critique

An ‘alternative hedonist’ politics of prosperity views our so-called ‘good life’ as not just environmentally disastrous but also in many respects undermining well-being rather than promoting it. It is a major cause of stress and ill health. It subjects us to high levels of noise and stench, and generates vast amounts of junk. Its work routines and commercial priorities mean that many people for most of their lives begin their days in traffic jams or overcrowded trains and buses, and then spend much of the rest of them glued to the computer screen, often engaged in mind-numbing tasks. A good part of its productive activity locks time into the creation of a material culture of ever faster production turnovers and built-in obsolescence, which pre-empts more worthy, enduring or entrancing forms of human fulfilment. It is therefore hardly surprising that some people even in the more affluent areas are now beginning to regret what has been lost in the pursuit of the dominant model of prosperity. Implicit in contemporary laments over lost spaces and communities, the commercial battening on children, the vocational dumbing-down of education, the ravages of ‘development’, the 'cloning' of our cities, and so forth, is a hankering for a society no longer subordinate to the imperatives of growth and consumerist expansion. Diffuse and politically unfocussed though this may be, it speaks to a widely felt sense of the opportunities squandered in recent decades for creating a fairer, less harassed, less environmentally destructive and more enjoyable way of life. [SLIDE 12]

‘Avant-garde nostalgia...’

To defend the progressive dimension of this kind of yearning (or what I term ‘avant-garde nostalgia’) against the exigencies of growth-driven 'progress' is not to recommend a more ascetic existence. On the contrary, it is to highlight the puritanical, disquieting, and irrational aspects of contemporary consumer culture. It is to speak for the forms of pleasure and happiness that people might be able to enjoy were they to opt for an alternative economic order. It is to open up a new ‘political imaginary’: a seductive vision of alternatives to resource-intensive consumption, centred on a reduction of the working week and a slower pace of living. By working and producing less we could improve health and well-being, and provide for forms of conviviality which harried and insulated travel and work routines make impossible. A cultural revolution along these lines would challenge the advertisers’ monopoly on the depiction of prosperity and the ‘good’ life. It would make the stuff that is now seriously messing up the planet – more cars, more planes, more roads, more throwaway commodities – look ugly because of the energy it squanders and the environmental damage it causes (Soper, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2020 esp.54-76); Soper, Ryle and Thomas, 2009; Soper and Trentmann, 2007). [SLIDE 13]

Perhaps show a film clip here from Yellow Dot:

The point is to look beyond the entrenched habitual ways of living, and to challenge all those who would ‘naturalise’ the consumerist lifestyle. The climate crisis is not just as a disaster looming but as an opportunity for breaking with many of the unpleasurable aspects of affluent ways of working and consuming.

My argument also highlights what people are beginning to experience themselves about the ‘anti’ or ‘counter’ consumerist aspects of their own needs and preferences; and draws out their implications for the consolidation of a broader systemic opposition to the existing order. [SLIDE14]

‘Structure of Feeling’

I have claimed some legitimacy for this approach by reference to what I term, following Raymond Williams, is an emerging ‘structure of feeling’ - in the emergence, that is, of an incipient critique of consumer culture and support for other greener and more pleasurable ways of living (Williams, 1977: 132, cf.128-136; cf. Gilbert, 2014: 151-3). The aim is to avoid moralizing: in its appeal to an already existing if relatively latent disaffection with the shopping mall culture ‘alternative hedonism’ is a form of immanent critique of consumer society that does not impute feelings to people, but seeks to respond to those already emergent within them.

I have compared the forms of enlightenment and personal epiphany this revolution will demand to those required in the case of other major historical movements for emancipation such as feminism, or the campaigns against slavery and racism (Soper, 2020: 185). Until very recently, however, our shopping habits have barely been challenged, nor has the work-and-spend way of living been provided with any countering ideal on our billboards and prime time TV. In the UK politics is thus still dominated by bi-party dispute over the means to a commonly agreed set of ends (economic growth, technological development, increased standards of living as defined by current consumer culture). The electorate has not been invited to reconsider the wisdom of those ends themselves nor their consequences for more peripheral societies. Nations with the least sustainable environmental footprint have long continued to be held out as ‘good life’ models for the developing nations, even as they imperil planetary life and cause the social disruption and migration that could end in ecological barbarism and even terminal forms of warfare. [SLIDE 15]

As Alf Hornborg has rightly noted, the notion that growth equates with progress

seems to lead some people to think that the issue of whether the planet will be inhabitable a hundred years from now is subordinate to indications that an increasing share of the world’s population is modestly improving its health, education, and purchasing-power. In this view, in other words, it does not seem to matter so much if we are generating changes that will lead to the extinction of our species, if increasing numbers of people today live somewhat longer, spend more years in school, and are able to consume a bit more than their parents (Hornborg, 2018: 42).

Environmental scientists and political economists have, of course, offered countering discourses. But many focus either on statistical details of the climate emergency and depletion of nature or on the alternative technologies and global institutions needed to limit or adapt to the damage; and in much of this argument, there is a presumption either that green technology, if implemented fast enough and on a large enough scale, will secure a future in which we continue to live and consume much as before (Soper, 2020: 2, 40-1; Hickel, 2018, 2021: 126-145). Or, if it is accepted that affluent societies cannot continue in their former ways, it is often with regret - with a sense that the more austere consumption required of us will be to our disadvantage (for some exemplification, see Soper, 2020: 12).

There have also of late been some highly negative developments (the destructive impact of Bolsanaro’s rule in Brazil, Milei’s electoral victory in Argentina, the now serious prospect of a second Trump Presidency in the US, and the general hardening of late of rightwing resistance to the green agenda notably in the UK under Sunak’s leadership of the Conservatives).

Yet despite all this, and the intense culture war efforts on the right to disparage ‘woke’ greens and their eco-benign projects, progress has been made – and made with significant support from the general public. A majority in London, for example, still approve the extension of ULEZ (Mayor of London Assembly, 2023), 62% in the UK would support their local authority adopting a target to make their area a 15 minute neighbourhood (Road Safety GB, 2023), and around 70% want government to stand by the commitment to net zero emissions by 2050 (YouGov Poll, 2023). Attitudes have to this extent been changing in recent years, and they are now meeting up with the more long term, if still minority, concerns noted above about the downsides of the fast-paced, acquisitive lifestyle for consumers themselves. The post-consumerist arguments of previously disregarded groups such as the Degrowth network or the Next System in the US are also finding more of a register in mainstream media. So, too, are those of the Parties and NGOs and supportive theorists campaigning not only for new forms of commoning and a more participatory economic order, but also for the revised thinking on well-being and consumption that would provide its politico-cultural support. Scientists are likewise giving higher profile in their addresses to the public to the need for an alternative politics of prosperity. In a message from over 11,000 of them emphasising the urgency of ‘major transformations in the ways our global society functions and interacts with natural ecosystems’, they claimed that such changes, together with social and economic justice for all, promise ‘far greater human well-being than does business as usual’(World Scientists’ Warning, 2019; IPPC, 2020).

In this context, a cultural politics emphasising the rewards of moving to slower-paced ways of working, rather than a wholly work-free existence; to fewer cars and more provision for bikes and public transport; to less tech-dependent and more humanly oriented systems of caring and education; and to providing instrinsically valued sources of well-being rather than more material acquisitions is, I suggest, more likely to meet with approval. Recourse to automation in some areas will certainly free up time, spare us of some of the more laborious tasks, and help to further breakdown the gender division of labour. But we could also explore the potential of a less intensive work culture for introducing more job sharing and gratifying forms of work, evolving new skills and reverting to some earlier ways of doing and making (Autonomy 2019; Bunting, 2004; Coote, 2014; Coote and Franklin, 2013; Frayne, 2016a, 2016b; Gorz, 1999; Hayden, 2013; Hester, 2017; Weeks, 2011). Such ways of working are compatible with communally owned enterprises and cooperatives in which labour is not subject to the imperative of maximising profit by reducing labour time. They could also draw on hybrid production practices that combine the most advanced green technologies in such fields as medicine, transport, energy provision, with older methods, more craft-based labour processes and slower mobility. This would allow more time to people to provide for themselves, and more space could be made available to them for gardening, workshops, cultural activities and recreation. Artisanal production could expand, and many more – including many who may be currently excluded by reason of illness or disability - would be able to benefit from the particular skills and forms of concentration in work and self-fulfilment it can provide (Sennett, 2006, 2009). A post-work order along these lines, supported by some form of UBI or citizen’s income, could well prove popular with the electorate and should be made central to the political imaginary of all campaigns promoting a green renaissance (BIEN 1986-present, Great Transition Initiative Forum on Basic Income, 2020; Autonomy interviews on UBI, 2019; Moulier-Boutang, 2004:152-166; Gorz, 1999: 100-110; Purdy, 2007).

Juliet Schor on ‘Plenitude’

As the American economist, Juliet Schor, has put it, [SLIDE 16] defending her view of cooperative ‘plenitude’ against ‘business as usual’:

We are circling back and plenitude is a synthesis of the pre- and postmodern. From the former it borrows the vision of skilled artisans producing for their own use as well as for the market (…). From the postmodern period comes advanced technology and smart, ecologically parsimonious design. It’s the perfect synthesis. Technology obviates the arduous and back-breaking labour of the preindustrial. Artisan labour avoids the alienation of the modern factory and office (Schor, 2010: 127).

This prospect for the future is at odds with the tech-utopian vision of a post-capitalist world in which automation will have largely freed people from the need to work and the Marxist promise of communist abundance for all would be realised (Bastani, 2018; Mason, 2015; Srnicek and Williams, 2016). It is therefore liable to be dismissed as overly limited and parochial – as belonging within a ‘folk politics’ of the kind that Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams have claimed embody ‘strategic assumptions that threaten to debilitate the left’, lead to failure and are incapable of transforming capitalism’ (Srnicek and Williams, 2016: 10-11). The critics of ‘folk politics’ are understandably frustrated with the ineffectuality of anti-capitalism activism over the last two decades, and the failure of the left to maintain a more concerted and systemic movement of opposition is surely in part to blame. But there are also many factors that have come together over the same period to render it almost impossible to sustain that kind of movement and have ruled out any imminent supplanting of capitalism in the current context. At any rate, my own, if somewhat more pragmatic, view is that such progress as might be made in that direction will now depend on a prior, and probably quite extended period, of cultural revolution in attitudes to prosperity, consumption and the ‘good life’. With that in mind, I would therefore defend alternative hedonism as itself offering a strategic vision for the future – and one that might prove more effective precisely because of its humanist grounding in already experienced discontents and anxieties, and appeals to already emergent appetites for alternatives ways of living and working.

It is in this spirit that I call for a conception of prosperity that rejects endless growth while also resisting cultural regression, and in doing so echo critiques of Western ideas of progress and modernity developed in postcolonial and commoning studies. As already indicated, however, I do so with particular reference to the destructive impact of the consumerist model of the ‘good life’ and its baleful influence around the world. Nations whose citizens’ consumption grossly exceeds the planet’s carrying capacity, can no longer be held out as aspirational models for the rest of the world (Latouche, 2009; Hornborg, 2009: 237–262). Indeed, those societies with less industrialised but more sustainable methods of production and modes of consuming must surely begin to count as more progressive (Hickel, 2015, 2021: 251). And these nations themselves might begin to reposition themselves, and to be perceived, as in the vanguard by comparison with the overdevelopment of the imperial powers or metropolitan centres who have rendered them marginal and premodern. It is this reversal that is registered, at least implicitly, in the words of Nemonte Nenquimo, [SLIDE 17] co-founder of the indigenous and non-profit organisation, Ceibo Alliance, and first female president of the Waorani organisation in the Ecuadorian Amazon:

You forced your civilisation upon us, and now look where we are: global pandemic, climate crisis, species extinction and, driving it all, widespread spiritual poverty. In all these years of taking, taking, taking from our lands, you have not had the courage, or the curiosity, or the respect to get to know us. To understand how we see, and think, and feel, and what we know about life on this Earth (Nenquimo 2020).

A reworking of ideas of progress and development would offer new forms of representation of the relationship between tradition and modernity. In place of a stadial and evolutionist conception of history, a degrowth understanding committed to social justice and a fairer distribution of environmental resources requires a more complex narrative on the old-new divide, a transcendence of the current binary opposition between uncritical progressivism and elegiac nostalgia. A green renaissance along these lines would be based in the recollection and endorsement of the eco-friendlier practices and pleasures that are being swept away by capitalist ‘progress’ and its most recent neo-liberal attempts to eliminate such institutions as mutuals, credit unions, co-operatives and other forms of common ownership and management (Venn, 2018: 120; cf. Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010: 252-254). By reflecting on past experience in ways that highlight what is pre-empted by contemporary forms of consumption , an ‘avant-garde nostalgia’ would recast certain forms of retrospection as potentially progressive, and thereby stimulate desire for a future that will be at once be less environmentally destructive and more sensually gratifying. This is not to endorse a simplistic ‘back to nature’ ethic through which modern ‘excesses’ can be corrected by return to the ‘simple’ way of life. But it is to resist the chronocentrism that refuses to look to resources in the past that could help us in the formation of a more viable and enjoyable future. This chimes with Couze Venn’s critique of the idea of temporality as a ‘linear progression towards an anticipated future’ (Venn 2006: 6-10). Or as De Angelis has put it, one wants ‘not to replace new by old, but only to let the old speak to us in new terms’ (De Angelis, 2018: 17). The aim is to open up the prospect of an eco-benign politic that is neither overly committed to technology, on the one hand, nor overly retrospective in outlook on the other, but grounded in new ways of working and spending leisure time and the sensual and spiritual pleasures they can provide (cf. Venn, 2006: 138f.).

One manifestation of this alternative to growth-driven capitalism is already being realised in the interstices of the mainstream market through the expanding culture of what has been termed ‘collaborative’ or ‘connected’ consumption: networks of sharing, recycling, exchange of goods and service provision (including of banking and other financial services) that by-pass conventional commerce. Prompted in part by the financial crisis of 2008, these have helped to reduce carbon emissions and waste while at the same time creating more eco-sensitive communities and cooperative ways of living (Schor, 2010, 2013, Soper, 2020: 126-130). [SLIDE 18]

In a transition period, collaborative production and consumption…

In a transition period, such initiatives are acting as a check on the individualisation of consumption and finding ways of circumventing the obstacles it places in the way of shared and more collective use of goods and forms of transport. They also help to subvert the reach and intrusion of the increasingly personalised address of internet advertising. More generally, they check the dominant consumerist aesthetics of ‘newness’ by shunning high street led fashions and mass production in favour of clothes swopping, remakes and homemade goods. They might also in the process prove the hubs for exerting pressure on corporations to end reliance on sweat-shop labour and ever faster turn-over times, and to render them accountable for the pollution incurred in production: in short, to add significantly to the obstacles confronting continued accumulation (cf.Klein, 2014b).

Although most of his own discussion relates to instances in Latin America, such forms of collaborative withdrawal from mainstream markets in the US and Europe exemplify what De Angelis refers to as commoning ‘adapting, redeveloping and recreating new social connections’ wherever other forms of collaborative actions have been displaced (usually by market forces). And as such, it is both non-quixotically embedded within capitalism, and contributing to its subversion. It is, he writes, [SLIDE 19]

a form of social cooperation that resists the dominant

paradigm of modern life, that operates outside the code and

protocol of capitalist-dominated social cooperation; it is a form

of social cooperation in which profit for profit’s sake, expropriation

and competitiveness are not the dominant drivers of the

forms and goals of cooperation, and that thus provides fundamentally

different meanings and sustenance for life in common (De Angelis, 2018: 207-8).

Such collaborative ways of providing for needs also rely upon, and help to promote a more communally oriented and republican spirit.

Of course, together with any resurgence of the republican ethos, comes the risk that notions of the ‘common interest’ and ‘collective good’ will be appropriated ideologically in problematic and politically partial ways. Something of this has already been seen in the peri-pandemical ‘culture wars’ and it is likely to continue into the post-coronaviral era. Nonetheless, the reassertion of the common good and revaluation of citizenship and public ownership, will be critical to the promotion of an alternative politics of prosperity. What needs emphasising here, as Venn has noted, is the disinheritance of a commonwealth and public impoverishment that has followed from the ever increasing privatisation in neoliberal times: [SLIDE 20]

…public works and amenities were the aggregate product of a whole community’s labour, paid for by means of general taxation, and should be regarded as forms of common pool resources, enhancing the capabilities of the people as a whole and conditioning the wellbeing of all. Their status as common wealth, that is, as collectively held goods and resources, should grant them the quality of an inalienable inheritance. Their increasing privatisation in neoliberal times is thus a process of

disinheritance that impoverishes everyone (Venn, 2018: 22).

This has been particularly true of a society such as the UK, where the ideological collapse of citizenship into a form of personally empowering consumption has provided the rhetorical cover for encroaching privatisation of services, depletion of them, and capitalist exploitation of increasingly individualised forms of commerce. Conversely, however, the consumer needs now to be recognised as a relatively autonomous agent whose self-interests can also extend to and encompass collective goods.

We must also accept, as consumer-citizens, that all of us alive today, but especially the more affluent, have a special responsibility to the up and coming generation and to all those who have yet to be born (cf.Krznaric, 2021a, 2021b). In the light of this accountability to the future, it is unclear why wasteful and vandalising forms of personal consumption, and the systemic encouragement of those, should remain exempt from the kinds of exposure and criticism that we now expect to be brought against racist, sexist, or blatantly undemocratic attitudes and behaviour. That thought may be discomfiting, even highly objectionable to many, and calls to curb individual consumption are still routinely rejected by liberal defendants of the market as authoritarian. Yet the growth-driven capitalist market has acquired its own totalitarian tendencies. Bent on marginalising whatever is not commercially viable, it dominates the time expenditure of the vast majority, monopolises the conception and aesthetic register of gratification, and is licensed to groom as many children as it can reach for a life of consumption. Indeed, it might better be seen at this stage in its evolution, not as a guarantor of universal freedoms and self-expression, but as a means of further extending the global reach and command of corporate power at the expense of the health and well-being of both the planet and the majority of its inhabitants. Confronting it will require, as Venn rightly claimed in After Capital, not only [SLIDE21]

opposed visions of a just society, but quite incommensurable understandings

of what it means to be human at all, implying a struggle over conflicting

perceptions of what is possible and what is equitable, thus a struggle over

disjunct political philosophies and imaginaries. Equally, it is a struggle about

defending hard-won political spaces and protecting socio-cultural common

wealth such as free public libraries and spaces, as well as about opening up

new spaces for inventing ways of being which have not and, indeed, could

not have existed before, since the technical, environmental and cultural

conditions of possibility for such a future were absent (Venn, 2018: 18).

How the conflict between these contrasting world outlooks unfolds over coming decades will be critical to the experience of all future generations.

(8,017 of which bibliography is 1,540 reading length: c.6,000)

pdf AGAINST THE COMMON GOOD: THE ROLE OF CAPITALIST CONSUMER CULTURE Kate Soper 2024

References

Amin A and Howell P eds. (2016) Releasing the Commons: Rethinking the Futures of the Commons, London: Routledge

Autonomy (2019) The Shorter Working Week: a Report. Available at: https://autonomy.work/portfolio/the-shorter-working-week-a-report-from-autonomy-in-collaboration-with-members-of-the-4-day-week-campaign/ (accessed 11 January 2024)

Autonomy (2019-2020) Interviews on Basic Income with David Frayne, Helen Hester, Nick Srnicek, Jamie Woodcock. Available at www.autonomyinstitute.org (accessed 11 January 2024)

Bastani A (2018) Fully Automated Luxury Communism. London: Verso

Beck U (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Trans. Ritter M. Sage: London

Bernstein J ed. (1991) The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture. London and New York: Routledge

BIEN (Basic Income Earth Network 1986-present). Available at: http://basicincome.org (accessed 11 January 2024)

Birch K (2020) Automated neoliberalism? The digital organisation of markets in technoscientific capitalism. New Formations 100-101: 10–27

Birch K and Bronson K (2022) Big Tech. Science as Culture 31 (1): 1-14

Bremmer I (2021) The Technopolar Moment: how Digital Powers Will Reshape the Global Order. Foreign Affairs: November/December. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/ian-bremmer-big-tech-global-order (accessed 8 January 2024)

Bunting M (2004) Willing Slaves: How the Overwork Culture is Ruling Our Lives. London: Harper Collins

Coote A (2014) Ten Reasons for a Shorter Working Week. (Available at: http://www.neweconomics.org (accessed 10 October 2023)

Coote A and Franklin J eds. (2013) Time on Our Side: Why We All Need a Shorter Working Week. London: New Economics Foundation

Caffenzis G and Federici S (2014) Commons against and beyond Capitalism. Community Development Journal 49(1): 92-105

Carrington D (2023) Revealed: Saudi Arabia’s plan to ‘hook’ poor countries on oil. Guardian: 27 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/nov/27/revealed-saudi-arabia-plan-poor-countries-oil (accessed 7 January 2024)

Chancel L., Bothe P and Voituriez T. (2023) Climate Inequality Report 2023, World Inequality Lab Study 2023/1. Available at: https://wid.world/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/CBV2023-ClimateInequalityReport-2.pdf (accessed 8 January 2024)

Clarke S (2017) How Green are Electric Cars ?. Guardian: 21 September.

Cruddas J (2018) The humanist left must challenge the rise of cyborg socialism. New Statesman 23

Dardot P and Laval C (2019). Common: On Revolution in the 21st Century, trans. MacLellan M, London: Bloomsbury

Dasgupta Review (2021) Final Report – the Economics of Bio-Diversity. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review (accessed 11 January 2024)

De Angelis M (2018) Omnia Sunt Communia. London: Zed Books

Domhoff W (2021) Who Rules America ? London and New York: Routledge

Frayne D (2016a) The Refusal of Work. London: Zed Books

Frayne D (2016b) Stepping outside the circle: the ecological promise of shorter working hours. Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism 20 (2): 197-212

Foucault, M (1982) The Subject and Power. Critical Inquiry 8 (4): 777-795

Foucault, M (2008) The Birth of Biopolitics. Trans. Birchall G. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan

Galloway S (2018) The Four. London: Penguin

Gilbert J (2014) Common Ground: Democracy and Collectivity in an Age of Individualism. London: Pluto Press

Global Fuel Economy Initiative (2023) Report . Available at: https://www.globalfueleconomy.org/ (accessed 9 January 2024)

Gorz A (1999) Reclaiming Work: beyond the wage-based society. Trans. Turner C. Cambridge: Polity Press

Great Transition Initiative Forum on Basic Income (2020) Universal Basic Income: Has the Time Come ? Available at: https://greattransition.org/gti-forum/universal-basic-income (accessed 11 January 2024)

Haug W F (1986) Critique of Commodity Aesthetics. Cambridge: Polity

Hayden A (2013) Sharing the Work, Sparing the Planet: Work-Time, Consumption and Ecology. London: Zed Books

Hester H (2017 )Demand the Future-Beyond Capitalism, Beyond Work. Available at: Demand the Impossible https://www.demandtheimpossible.org.uk (accessed 8 January 2024)

Hester H and Srnicek N (2023) After Work: a History of the Home and the Fight for Free Time. London: Verso

Hickel J (2015) Forget ‘developing’ poor countries, it’s time to ‘de-develop’ rich countries. Guardian: 23 September

Hickel J (2018) Why Growth can’t be green. Foreign Policy 12 September.

Hickel J (2021) Less is More: how degrowth will save the world. London: Windmill Books

Hornborg A (2009) Zero-sum world: Challenges in conceptualizing environmental load displacement and ecologically unequal exchange in the world system. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 50(3–4)

Hornborg A (2018) Nature, Society and Justice in the Anthropocene: Unravelling the Money-Energy-Technology Complex. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Horton H (2023) Motor emissions would have fallen 30% more without SUV trend, report says. Guardian: 24 November

Hurst A (2023) Paris is saying ‘non’ to a US-style hellscape of supersized cars – and so should the rest of Europe. Guardian: 16 December 2023

IPPC Report (2020) Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/reports/ (accessed 11 January 2024)

Klein N (2014a) This Changes Everything. New York: Simon and Shuster

Klein N (2014b) Climate change: how to make the big polluters really pay. Guardian: 17 October

Krznaric R (2021a) To Safeguard the Future we must learn how to be better Ancestors. Guardian : 12 February

Krznaric R (2021b) The Good Ancestor: How to think Long Term in a Short Term World. London: Allen Lane

Latouche S (2009) Farewell to Growth. Trans. Macey D. Cambridge: Polity Press

Lazzarato M (2009) Neoliberalism in Action: Inequality, Insecurity and the Reconstitution of the Social. Theory, Culture, Society 26 (6): 134-152

Lehrer M (1997) The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames and Hudson

Leiss W (1978) The Limits to Satisfaction: on Needs and Commodities. London: Marion Boyars

Lewis J (2013) Beyond Consumer Capitalism: Media and the Limits to the Imagination. Cambridge: Polity Press

Lodziak C (1995) Manipulating Needs: Capitalism and Culture. London: Pluto

Lowrie I (2016) On Algorithmic Communism. Los Angeles Review of Books: 8 January

MacNay L (2009) Self as Enterprise: Dilemmas of Control and Resistance in Foucault’s The Birth of Politics. Theory, Culture,Society 26 (6): 55-77

Marcuse H (1964) One-dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Boston: Beacon Press

Mariqueo-Russell A and Read R (2019) Fully automated luxury barbarism. Radical Philosophy 206: 108-110

Mason P (2015) PostCapitalism: a Guide to Our Future. London: Allen Lane

Mayor of London Assembly (2022) Nearly twice as many Londoners support extension of the ULEZ. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/media-centre/mayors-press-releases/nearly-twice-many-londoners-support-expansion-ulez (accessed 12 January 2024)

Mignolo W (2011) The Darker Side of Western Modernity, Global Futures, Decolonial Options. North Carolina: Duke University Press

Milanovic B (2019) Capitalism, Alone. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press

Moore M and Tambini D (2021) Regulating Big Tech. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Moulier-Boutang Y (2004) Cognitive Capitalism. Trans. Emery E. Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity Press

Nenquimo N (2020) This is my message to the Western world: your civilisation is killing life on earth. Guardian: 12 October

Philips P (2018) Giants. New York: Seven Stories Press

Srnicek N (2016) Platform Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity

Srnicek N and Williams A (2016 revised ed.) Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work. London: Verso

O’Connell M (2021) A Managerial Mephistopheles: inside the mind of Jeff Bezos. Guardian: 3 February

Oxfam (2020) Confronting Carbon Inequality report. Available at: https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/carbon-emissions-richest-1-percent-more-double-emissions-poorest-half-humanity# (accessed 9 December 2023)

Purdy D (2007) Citizens’ Income: Sowing the Seeds of Change. Soundings 35: 54-65.

Road Safety GB (2023) Public support for 15-minute neighbourhoods. Available at: https://roadsafetygb.org.uk/news/public-support-for-15-minute-neighbourhoods/ (accessed 12 January 2024)

Rose N (2001) The Politics of Life Itself. Theory, Culture, Society 18(6): 1-30

Rose N (2009) Power and Subjectivity: Critical history and psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Schor J (2004) Born to Buy, The Commercialised Child and the New Consumer Culture. New York: Simon and Shuster

Schor J (2010) Plenitude: London: Penguin

Schor J (2013) Connected Consumption: Slowing Down the Spending Treadmill. In Osbaldiston N. ed. Culture of the Slow: Social Deceleration in an Accelerated World. Basingstoke: Palgrave, Macmillan: 34-51.

Sennett R (2006) Culture of the New Capitalism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press

Sennett R (29) The Craftsman. New Haven and London: Yale University Press

Shiva V (2019) Bill Gates is continuing the work of Monsanto interview with France 24. (Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MNM833K22LM (accessed 11 January 2024)

Soper K (2006) Conceptualizing Needs in the Context of Consumer Politics. Journal of Consumer Policy 29 (4): 355-372

Soper K (2007) Re-thinking the ‘good life’: the citizenship dimension of consumer disaffection with consumerism. Journal of Consumer Culture 7 (2): 205-229

Soper K (2008) Alternative Hedonism, Cultural Theory and the Role of Aesthetic Revisioning. Cultural Studies 22 (5): 567-587

Soper K (2020) Post-Growth Living: for an alternative hedonism. London: Verso

Soper K, Ryle M and Thomas L eds. (2009) The Politics and Pleasures of Consuming Differently. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Soper K and Trentmann F eds. (2008) Citizenship and Consumption. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Stiglitz J (2013) The Price of Inequality. London: Penguin

Terranova T (2015) Introduction to Eurocrisis, neoliberalism, the common. Theory, Culture, Society 26 (6): 234-262

Tooze A (2023) The climate emergency really is a new type of crisis – consider the ‘triple inequality’ at the heart of it. Guardian: 23 November

Tyldesley J (2011) The Private lives of the Pyramid Builders at: bbc.co.uk/history/ancient (accessed 10 December 2023)

Van de Mieroop M (2021) A History of Ancient Egypt 2ndedn. London: Wiley Blackwell.

Venn C (2006) The Post-Colonial Challenge, Towards Alternative Worlds. London: Sage

Venn C (2018) After Capital. London: Sage

Weeks K (2011) The Problem With Work. Durham NC: Duke University Press

Wilkinson R and Pickett K (2010) Spirit Level: why Equality is better for Everyone. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Williams R (1977) Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press

World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency (2019). Journal of Bioscience: 5 November

YouGov Poll (2023) To what extent do you support or oppose the government's commitment to cutting carbon emissions to net zero by 2050? Available at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/survey-results/daily/2023/07/24/d3bc3/1 (accessed 12 January 2024)

Zuboff S (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. New York: Public Affairs

The book’s publication on 25 April is followed by book discussion groups and collaborative events with grassroots green collectives across the country.

“This is not the definitive conclusion of what wild service means,” says Hayes. “It’s a provocation – throwing it open to other people to define it. It is totally up to the reader. We’re just trying to say that belonging has an active dynamic to it.”

People are often desperate to help but overwhelmed by the scale of global heating and ecological breakdown. “We’ve been breastfed on leadership,” says Hayes. “People have forgotten their own collective community power. We’ve been taught that coming together is somehow seditious but it is the true power and the true way. It’s a democracy.”

note Note(s) liée(s)

12 juin 2024

12 juin 2024

Presentation of the notebook | Commoning beyond growth

12 juin 2024 3 juin 2024

3 juin 2024

Kate Soper

3 juin 2024Carnet(s) relié(s)

file_copy

61 notes

file_copy

61 notes

Commoning Beyond Growth

file_copy 61 notesAuteur·trice(s) de note

Contacter l’auteur·triceCommunauté liée

Commoning Beyond Growth

Plus d’informationsPublication

13 juin 2024

Modification

18 juin 2024 10:45

Licence

Attention : une partie ou l’ensemble de ce contenu pourrait ne pas être la propriété de la, du ou des auteur·trices de la note. Au besoin, informez-vous sur les conditions de réutilisation.

Visibilité

public

Pour citer cette note

Marie-Soleil L'Allier. (2024). Against the Common Good: the role of capitalist consumer culture. Praxis (consulté le 19 juillet 2024), https://praxis.encommun.io/n/_aVy7l5In7HZT9Y3FsRoTc8iDyM/.

shareCopier